A “breakthrough therapy” for depression.

That’s how the FDA recently referred to the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, psilocybin.

This was in light of a preliminary study done in 2016 that showed a substantial reduction in depressive symptoms in patients suffering from what researchers classified as “untreatable depression”.

Is psilocybin all it’s cracked up to be? Does it live up to the hype?

What Is Psilocybin?

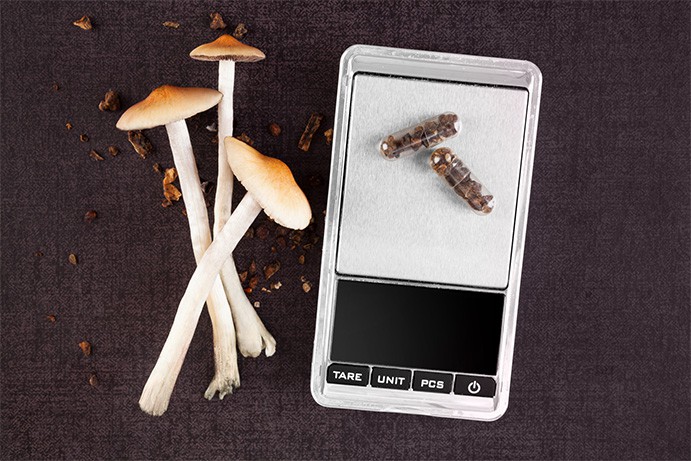

Psilocybin is an active psychoactive alkaloid in magic mushrooms. It can be found in a variety of different species but is most common in the Psilocybe genus.

These mushrooms have been used for thousands of years by various cultures in South America and Mexico, as a way to connect to the spirit world.

The hallucinogenic qualities of the mushrooms were thought to provide access to sacred knowledge, reserved for use amongst the local shamans.

Researchers have started investigating new applications of the mushroom. New applications including a treatment for depression and small doses as a nootropic are becoming more popular each year.

What’s The Hype Around Psilocybin All About?

Recently, the buzz about psilocybin as an antidepressant has started to gain momentum. This started directly following a research study sponsored by COMPASS Pathways, a large British Life Sciences company specializing in mental health.

The initial study focused on 12 patients with what researchers reported to be “treatment-resistant depression”. They gave subjects either high dose psilocybin (25 mg) or low-dose psilocybin (10 mg). At the end of the 6-week trial, depressive symptoms dropped an average of 61%.[1]Carhart-Harris, R. L., Bolstridge, M., Rucker, J., Day, C. M., Erritzoe, D., Kaelen, M., … & Taylor, D. (2016). Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(7), 619-627.

The only major problem with this study was that there wasn’t a control group to compare the subjects with a similar group NOT taking any psilocybin.

The results of the study were so positive, that the researchers leading the study were approved for a larger phase II clinical trial involving a much larger study group of 216 people spread over 12-15 different study sites. The plan, if all goes well, is to move on to a phase III clinical trial in 2020.

How Psilocybin Works

Using psilocybin as an antidepressant isn’t a new concept.

There’s evidence that people have been using psilocybin-containing mushrooms since the early Mayans. They used it in ceremonies and as a way of healing a damaged soul, which many scholars believe may have been an early diagnosis of depression.

In 2013 a study was published highlighting the specific mechanisms involved with the psilocybin molecule that gives us insight into how it may affect depression, as well as a myriad of other important cognitive functions.

The study reported that psilocybin was first converted in the liver to a secondary metabolite called psilocin. This compound then went on to activate the 5HT2a receptors in the brain. These receptors are otherwise known as the serotonin receptors, which play an important role in human physiology.[2]Sarris, J., McIntyre, E., & Camfield, D. A. (2013). Plant-based medicines for anxiety disorders, part 2: a review of clinical studies with supporting preclinical evidence. CNS drugs, 27(4), 301-319.

Many of the effects, both psychoactive and therapeutic stem from this effect.

Psilocybin has an especially prominent effect on the prefrontal cortex of the brain.[3]Carhart-Harris, R. L., Erritzoe, D., Williams, T., Stone, J. M., Reed, L. J., Colasanti, A., … & Hobden, P. (2012). Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(6), 2138-2143.

This is the area associated with side effects of distortion in the perception of time and hallucinations which are characteristic of larger doses of the compound. Interestingly, this activity is also likely to be at least partly responsible for the antidepressant effects of the compound.

Studies have shown that psilocybin can reduce blood flow to the prefrontal cortex of the brain. Hyperactivity in this region is often associated with depressed individuals, suggesting psilocybin as a potential treatment for the condition, as measured on a physiological level.[4]Carhart-Harris, R. L., Erritzoe, D., Williams, T., Stone, J. M., Reed, L. J., Colasanti, A., … & Hobden, P. (2012). Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(6), 2138-2143.

How Psilocybin Compared To Other Antidepressants

There are hundreds of antidepressant compounds currently available, but the one that stands out above them all, are the SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors).

These drugs work on the same 5-HT2a receptors that psilocybin works on, but with slightly different effects.

SSRIs work by preventing the reuptake and destruction of serotonin, causing an overall increase in serotonin activity. Psilocybin, on the other hand, activates these receptors directly. Both result in an increase in serotonin activity specific to the 5HT2a receptors.

Euphoria is one of the most reliable effects of the compound, which is likely due to this interaction with serotonin receptors in the brain.

Other Neurological Benefits Of Psilocybin

Although more research is needed to confirm before this information can be taken as fact, there are several other potential benefits offered by psilocybin activity in the brain.

Overall, 5-HT2a receptor stimulation and psilocybin consumption have been associated with:

1. Enhanced cognitive flexibility[5]Boulougouris, V., Glennon, J. C., & Robbins, T. W. (2008). Dissociable effects of selective 5-HT 2A and 5-HT 2C receptor antagonists on serial spatial reversal learning in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(8), 2007.

This is the ability to switch between thinking about 2 separate tasks or thinking about several different activities at the same time.

2. Enhanced associative learning[6]Harvey, J. A. (2003). Role of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in learning. Learning & Memory, 10(5), 355-362.

This is the type of learning that develops in response to a stimulus in our environment. The classic example is that of Pavlov’s dogs, who learned to begin salivating at the sound of a bell.

3. Enhanced cortical neural plasticity[7]Vaidya, V. A., Marek, G. J., Aghajanian, G. K., & Duman, R. S. (1997). 5-HT2A receptor-mediated regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in the hippocampus and the neocortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 17(8), 2785-2795.

Neural plasticity is the process of reorganizing neural connections in the brain. It’s been the subject of a lot of study lately and is highly debated. Another nootropic mushroom, lion’s mane, has also been reported to offer this complex and fascinating process, however, research is still in the early stages and is inconclusive.

4. Sustained improvements in overall well-being[8]Buchborn, T., Schröder, H., Höllt, V., & Grecksch, G. (2014). Repeated lysergic acid diethylamide in an animal model of depression: normalisation of learning behaviour and hippocampal serotonin 5-HT2 signalling. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 28(6), 545-552.

This was measured by having participants take 2 or 3 sessions of moderate to high-dose psilocybin and went through a series of follow-ups over 14 months. 64% of the participants in this study indicated that the experience increased self-reported overall well-being and life satisfaction.

A Note On Microdosing Psilocybin

There is an (unofficial) group of psilocybin users promoting the idea of microdosing as a form of nootropics.

This involves taking very small doses of the compound daily to receive cognitive enhancing benefits.

At doses of around 300 mg dried mushroom (equivalent to around 3 mg psilocybin) little to no psychoactive effects are experienced.

It’s not clear whether this dosage is going to have enough effect to produce improvements in cognitive function, however, there have not yet been any studies to confirm or dispute this.

The lowest dose used in scientific research is around 10 mg of psilocybin, which is equivalent to about 1 g of raw magic mushrooms. To put this into context, this is about a third of the normal psychoactive dose.

As mentioned. 5HT2a receptor activity has been linked with a range of cognitive enhancement effects, including cognitive flexibility, and associative learning.

What Does This Mean?

Although we’re still awaiting the results of the phase II portion of the COMPASS Pathways trial, there’s a mountain of evidence forming to support both antidepressant and potential nootropic benefits from psilocybin-containing mushrooms.

One of the most interesting implications if these clinical trials prove legitimate medicinal use is that the FDA and other regulatory agencies will need to revisit the drug schedule I status.

A compound included in the Schedule I category are considered addictive, dangerous, and without valid medicinal value. No schedule I drugs are legal for anything except highly regulated research studies.

Confirmed medical benefits of the compound will, therefore, require regulators to move it into a lower restriction level.

There’s a lot of research still needed to truly understand how this incredible molecule works, and how we may apply it to medical and supplemental regimens to better our lives and stave off depression.

Micro-dosing is still in its infancy but shows potential as a future nootropic supplement.

Originally posted on November 2, 2018, last updated on March 31, 2024.

References

| ↑1 | Carhart-Harris, R. L., Bolstridge, M., Rucker, J., Day, C. M., Erritzoe, D., Kaelen, M., … & Taylor, D. (2016). Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(7), 619-627. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Sarris, J., McIntyre, E., & Camfield, D. A. (2013). Plant-based medicines for anxiety disorders, part 2: a review of clinical studies with supporting preclinical evidence. CNS drugs, 27(4), 301-319. |

| ↑3, ↑4 | Carhart-Harris, R. L., Erritzoe, D., Williams, T., Stone, J. M., Reed, L. J., Colasanti, A., … & Hobden, P. (2012). Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(6), 2138-2143. |

| ↑5 | Boulougouris, V., Glennon, J. C., & Robbins, T. W. (2008). Dissociable effects of selective 5-HT 2A and 5-HT 2C receptor antagonists on serial spatial reversal learning in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(8), 2007. |

| ↑6 | Harvey, J. A. (2003). Role of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in learning. Learning & Memory, 10(5), 355-362. |

| ↑7 | Vaidya, V. A., Marek, G. J., Aghajanian, G. K., & Duman, R. S. (1997). 5-HT2A receptor-mediated regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in the hippocampus and the neocortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 17(8), 2785-2795. |

| ↑8 | Buchborn, T., Schröder, H., Höllt, V., & Grecksch, G. (2014). Repeated lysergic acid diethylamide in an animal model of depression: normalisation of learning behaviour and hippocampal serotonin 5-HT2 signalling. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 28(6), 545-552. |

Leave a Reply